When her Notre Dame varsity basketball season ended in 1978, Dr. Carol Lally Shields ’79 shifted her competitive focus to stacking her bookstore basketball team “bigtime” with one of the best players on campus. She was pretty sure that fellow teammate forward Sue Kunkel ’80 would complement her own guard play.

“I knew she would rip down every rebound,” Lally Shields says. They won the entire women's side of the tournament.

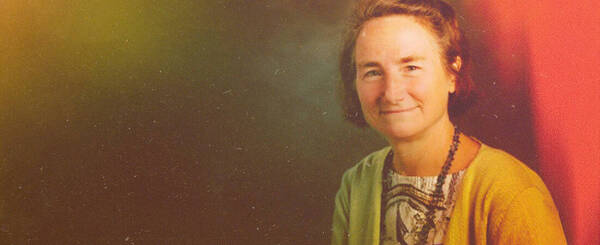

Lally Shields has applied the same level of competitiveness and drive to her career in medicine. Most recently, the NCAA awarded Lally Shields with the 2023 Theodore Roosevelt Award — the highest honor the NCAA may confer upon an individual — presented annually to a distinguished person of national reputation and exceptional accomplishment.

A native of western Pennsylvania, Lally Shields dreamed of attending the best college possible – which, at the time in her hometown, meant the University of Notre Dame. Though she was a member of Kennedy Christian High School’s girls basketball team, her ambitions remained academic in nature.

“I applied with zero intentions of playing sports. I wanted to become a doctor and I wanted to study,” Lally Shields says.

She would achieve those goals and more. Though only one or sometimes two students at Kennedy Christian gained admission to Notre Dame each year, she was accepted — turning down scholarships to run track at Case Western Reserve and the University of Pittsburgh to attend the school of her dreams. The sixth of eight children, Lally Shields recalls her older brother, Mike ’73, driving her six hours to campus to drop her off for orientation. She moved herself into Farley Hall — a record player, a typewriter, and a slide rule comprising some of her key possessions — and started classes, including the legendary professor Emil T. Hoffman’s chemistry course. One day after class, she spotted a piece of notebook paper taped to the stairwell in Farley: “Announcement. Women’s basketball tryouts. Come if you’re interested,” it read.

“At first I thought, nah, no way. Too busy,” Lally Shields recalls.

At the time, Notre Dame did not have a varsity women’s basketball team. Even though Lally Shields had played the sport her entire life — including street ball with her five brothers where she could slip a drive and shoot a jump shot as good as the rest of them — she figured the time commitment would distract from her studies. Yet with each time she went up the stairwell, the little piece of paper began to bother her. She decided to try out.

She made the team.

The squad had humble beginnings. Starting out as a club, they drove to away games in a rented van, stayed in cheap hotels, and ate McDonalds while on the road, sometimes struggling to compete. Often, they practiced in the “rubber gym” in the basement of the Athletics and Convocation Center, since the men had priority to use the main floor. Thanks to Title IX — the federal civil rights law passed in 1972 that prohibits sex-based discrimination in any education program that receives funding from the federal government, including sports — the team successfully petitioned the University to become an official varsity sport by her junior year.

Lally Shields and her teammates slowly built the foundation for the future legacy of Notre Dame women’s basketball. Things began to change. The team received nicer uniforms, stayed in better hotels, and finally all had the same shoes — Nikes with a green stripe (Lally Shields still has her pair). They started playing more reputable teams. By her senior year, the team had even brought in recruits.

A three-time captain, Lally Shields led the Irish with 12.8 points per game in her final season, and became the first female student-athlete to receive the Byron V. Kanaley Award for excellence in academics and leadership, the highest honor given to Notre Dame student-athletes. The perseverance and determination required to build up the program extended to Lally Shields’ career trajectory after her time at Notre Dame.

“All that grit … practice, missing parties, studying … trained me to be really good at time management. It also boosted my self esteem and gave me a whole nucleus of friends that I would have never met,” Lally Shields says.

Lally Shields was firm in her goals of becoming a doctor, having grown up with parents and siblings in the medical field. While excelling on the court, she was just as dedicated to her studies, choosing a quiet seat on the back of the bus to do her homework, occasionally singing along to Paul Simon’s “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover,” a team favorite. After graduating, she went on to earn her medical degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1983. Unsure what to specialize in, she phoned her older brother, Pat ’75, who encouraged her to consider ophthalmology. He spoke of the beauty of allowing someone the ability to see the world with only one surgery. Lally Shields was easily convinced and open to the challenge.

“Always striving for my best, playing my best game, never saying no and doing the extra ladder drill so I could be a little bit stronger … I’ve done that in my career, too,” says Lally Shields.

She believes her basketball career helped her gain admission into the highly competitive ophthalmology residency program at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, the opportunity that would form the groundwork for her world-renowned research in ocular oncology — a subspecialty where she believed she could save lives. She felt a trust in herself that she could perform the highly intricate and challenging surgeries.

“I’m good enough to play basketball for Notre Dame,” she recalls reminding herself. “Why wouldn’t I want to do this? It’s a challenge, and I’m saving lives. I trusted myself like I did then.”

Alongside her husband, Dr. Jerry Shields, the two specialists care for nearly half of the nation’s children who are diagnosed with retinoblastoma each year and around one-third of the adults who are seeking treatment for ocular melanoma. Lally Shields has authored or co-authored 15 textbooks and more than 2000 peer-reviewed medical articles in these areas. In 2004, she was the first woman to receive the Donders Medal, given every five years by the world-renowned Netherlands Ophthalmological Society. She is also one of only a handful of doctors to focus on ocular tumors full-time.

Lally Shield’s life came full circle when she treated a fellow Domer’s baby who was suffering from potential retinoblastoma. An R.A. in Farley, Lally Shields remembered her resident who had impaired vision, but never knew the cause. Now, years later, she had traveled across the country to seek care for her newborn child, knowing that Lally Shields was an expert in treating the disease. Lally Shields has gone on to treat many Domers, and even talks Notre Dame sports with current ophthalmology resident at Wills Eye Hospital, Leo Hall ’14.

Lally Shields encourages current Notre Dame students to remember that no career is too big or too small. Whatever it is, “you should give your best.” She is grateful to Notre Dame for not only her education, but also for nurturing her belief in herself.

“I wanted to be a doctor. I wanted to be a good doctor. And I just followed my path and followed my heart and my dream came true,” she says.

by Allie Griffith '17, '19 M.Ed.